Environmental Policy & Law

Environmental policies and laws are critical tools for protecting ecosystems in the face of growing threats like climate change, biodiversity loss, and unchecked urbanization. This section explores how legal frameworks, regulatory decisions, and Indigenous-led governance models shape the management of land and natural resources. Through case studies such as the wildfires in Jasper National Park, we examine successes, gaps, and opportunities for more sustainable policy-making. These insights are especially relevant for vulnerable spaces like the David Dunlap Observatory lands.

Wildfires Ravage Jasper

Ariane Blouin

🕒 Estimated reading time: 8-10 minutes

Wildfires have seen a significant rise in both frequency and intensity. This increase is directly linked to rising global temperatures caused by climate change. In Jasper National Park, wildfires have serious impacts on visitor experiences, local communities, biodiversity, carbon emissions, and Indigenous populations. To address this crisis, it is essential to take action by promoting ecological restoration, cultural burning led by Indigenous stewardship, and prescribed fires supported by new legislation that enables these practices.

Keywords: Wildfires, Climate Change, Restoration, Cultural Burning, Prescribed Fires

Introduction

Climate change caused by human activity is responsible for the rise in global temperatures. This warming trend intensifies drought cycles, characterized by increasingly extreme heat and lack of rainfall (2). As a result, wildfires are becoming more frequent and more severe in many parts of the world—including in Canada.

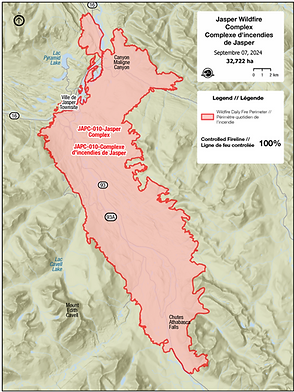

Canada is experiencing widespread wildfires that are growing in scale year after year. Western Canada is particularly affected, and Jasper National Park in British Columbia has not been spared (3). As of July 2024, the fire perimeter in Jasper had reached 278.03 km, covering an area of 32,722 hectares (see Figure 1). These fires have had negative impacts on tourism, the economy, the environment, and cultural heritage in Jasper National Park.

Figure 1. Map of the Jasper wildfire complex (3).

2024 – Tourism and Economy

Visitor Experience in the Park

Wildfires have severely impacted visitors and users of Jasper National Park. In recent years, many park facilities have been affected, including accommodation establishments, campgrounds, and hiking trails (3). These disruptions directly affect the visitor experience for those who come to explore Jasper. Park authorities have had to restrict or completely close access to certain areas (4).

In addition, several preventive safety measures have been put in place to protect visitors and reduce wildfire risk. For example, lighting or maintaining fires is strictly prohibited in designated areas, and access to certain zones or roads considered dangerous has been temporarily banned (4).

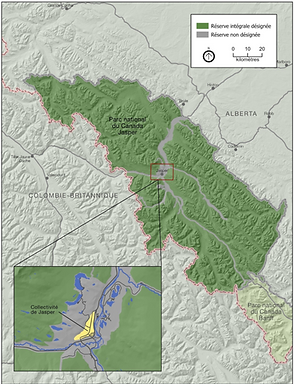

Figure 2. Jasper National Park (5).

The Local Population of Jasper

The wildfire situation has also had a serious impact on the local population of Jasper. Since the town is located in the heart of the national park (see Figure 2), residents have been directly affected by the consequences of the fires.

In July 2024, the fire extended beyond the park boundaries: officials estimated that between one-third and one-half of the buildings in the town of Jasper were damaged or destroyed by the wildfire (see Figure 3). This has had devastating effects on the local economy as well as on the mental and physical health of the town’s residents. Wildfires now represent a major public safety issue for the community of Jasper.

Figure 3. Jasper National Park — Canadian Press (6).

Environment

Biodiversity and Natural Habitats

Wildfires in Jasper National Park, driven by climate change, are severely impacting biodiversity. These fires are a major cause of natural habitat loss, and they also contribute to the extinction of species (7). Many species are forced to relocate after fires, and in some cases, they do not survive. This disruption affects not only individual species, but also the ecological interactions that sustain the park’s ecosystems.

Forests and Carbon Sinks

Biodiversity is not the only environmental factor affected by wildfires. When vast stretches of forest burn, they release large quantities of carbon into the atmosphere, because trees act as carbon storage systems through the process of photosynthesis (2). Thus, forests suffer from climate change, but they also intensify climate change when they burn (2). Forests are true carbon sinks, and wildfires release that stored carbon, contributing to a vicious climate feedback loop.

Figure 4. Twisted Pine – The most common tree species in Jasper (8).

Figure 5. Natural habitat before the fire, Jasper National Park (1).

Culture

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous communities are deeply affected by wildfires. Since many of these communities are located in forested regions, the increasingly dry summer seasons place them in dangerous and vulnerable situations. One striking example is the Elephant Hill wildfire of 2023, which burned through 200 hectares of land belonging to various Indigenous communities (9). These fires not only threaten lives and property, but also disrupt cultural practices, land-based traditions, and the spiritual relationship Indigenous peoples have with their territories.

Figure 6. Elephant Hill Wildfire, June 2023 (10).

Proposed Solutions

Ecological Restoration Using Ancestral Indigenous Techniques

There is much to learn from Indigenous knowledge systems. In June 2023, several Secwépemc communities in Kamloops, British Columbia, gathered to discuss post-wildfire species restoration, particularly in response to damage from the Elephant Hill fire (9).

From an Indigenous perspective, post-fire restoration is conducted with ecological—not economic—goals in mind (9). The aim is to rehabilitate ecosystems in a healthy and balanced way, with a focus on planting species that naturally slow the spread of fire due to the high water content in their tissues (9). Reforesting with a diverse mix of trees and shrubs helps establish moister habitats, reducing the likelihood of future wildfire ignition (10).

Figure 7. Ecological restoration in practice (10).

Cultural Burning and Indigenous Fire Stewardship

Cultural burning, also known as Indigenous fire stewardship, is a traditional practice that has been used for millennia by Indigenous communities (10). These controlled, low-intensity fires are used to reduce wildfire risk by burning underbrush—the primary fuel for large wildfires (10).

Beyond risk mitigation, cultural burning improves habitats by eliminating disease in vegetation and creating natural firebreaks (10). However, this knowledge has historically been suppressed by colonial governments, and such practices remain heavily restricted today (10).

While Parks Canada claims it is working in collaboration with Indigenous communities to implement cultural burning (11), in reality, all documented initiatives have been led by Parks Canada and were prescribed burns, not true cultural burns—meaning they lacked Indigenous governance and stewardship (11).

Figure 8. Cultural burning team near traditional Yunesit’in territory, British Columbia (12).

Figure 9. Prescribed burn conducted by Parks Canada (13).

“Indigenous fire use must be legalized. Understory burning is not harmful. We’re not trying to kill trees—we’re simply bringing back medicine and forage, making communities safer because there will be far fewer fires with this practice.”

— Joe Gilchrist, Indigenous Knowledge Trainer and Fire Keeper (12)

Prescribed Burning

Prescribed burning, also known as controlled burning, is a fire management technique based on Western scientific knowledge (11). Its primary goal is to reduce wildfire risk, though it is also employed for other ecological purposes (11).

These operations are always led by government or scientific agencies, such as Parks Canada. In 2023, Parks Canada’s prescribed burning program treated 532 hectares across six different national parks (13).

Table 1. Key Differences Between Cultural Burning and Prescribed Burning (11).

Conclusion

In conclusion, wildfires represent a major challenge for the tourism, economy, environment, and cultural fabric of Jasper National Park. Rising temperatures caused by climate change are intensifying drought periods, leading to increasingly severe wildfire seasons. These fires have devastating effects not only on the park’s forests and biodiversity, but also on the local population of Jasper, visitors, and Indigenous communities.

This collective crisis poses a threat to public safety and the natural habitats that define the park. Action must be taken now to curb the rising frequency and intensity of wildfires.

Promoting ecological restoration guided by Indigenous traditions, legalizing cultural burning, and increasing the number of prescribed burns are realistic and effective strategies to reduce wildfire risks in Jasper National Park.

Bibliography

-

Nudd, A. (2024, mars 25). 10 things you can’t miss on your first visit to Jasper [Photographie]. Dirt In My Shoes. https://www.dirtinmyshoes.com/10-things-cant-miss-first-visit-jasper/

-

Ball, D. (2021, juillet 3). Les changements climatiques remettent en question la gestion des feux de forêt. Radio-Canada. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1806375/feux-foret-lytton-incendie-gestion-changements-climatiques

-

Gouvernement du Canada. (2024, 17 septembre). Situation sur les feux de forêt : complexe d’incendies de Jasper. Parcs Canada. https://parcs.canada.ca/pn-np/ab/jasper/securite-safety/feux-alert-fire-feudorref-wildfire

-

Gouvernement du Canada. (2009, 3 décembre). Lois codifiées : Règlement sur la prévention des incendies dans les parcs nationaux du Canada. Site Web de la législation (Justice Canada). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/fra/reglements/DORS-80-946/page-1.html

-

Gouvernement du Canada. (2023, 23 novembre). Plan directeur du parc national du Canada Jasper. Parcs Canada. https://parcs.canada.ca/plan-mangement/plan/involved/plandirecteur-mgtnplan

-

La Presse canadienne. (2024, 25 juillet). Les feux de forêt font rage et se brûlent près de la moitié de la ville de Jasper. Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/environnement/817056/feux-foret-atteignent-jasper

-

United Nations. (n.d.). Pourquoi la biodiversité est Action Climat. https://www.un.org/fr/climatechange/science/climate-issues/biodiversity#:~:text=Let’s%20end%20extinction%20together%2C%20co%C3%BBtier

-

Arbres Canada. (2017, 15 décembre). Alberta – Pin tordu. Les arbres officiels du Canada. https://arbrescanada.ca/resources/arbres-officiels-au-canada/alberta-pin-tordu/

-

WWF. (2023, 6 juillet). Voici pourquoi la restauration menée par les Autochtones après des feux de forêt fonctionne. World Wildlife Fund Canada. https://wwf.ca/fr/stories/la-restauration-menee-par-les-autochtones-apres-des-feux-de-foret-fonctionne/

-

Roque, L. (2024, 25 septembre). La restauration menée par les Autochtones réduit la menace des prochaines saisons d’incendies. World Wildlife Fund Canada. https://wwf.ca/fr/stories/la-restauration-menee-par-les-autochtones-reduit-la-menace-des-prochaines-saisons-dincendies/

-

Gouvernement du Canada. (2024, 14 août). Intendance autochtone du feu. Parcs Canada. https://parcs.canada.ca/nature/science/conservation/feu-fire/autochtones-indigenous

-

Brend, Y. (2022, 29 juin). Brûlages traditionnels : Combattre les feux de forêt par le feu. Espaces autochtones, Radio-Canada. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/espaces-autochtones/189423/incendies-foret-tradition-autochone-brulage-dirige-feu-terre-ecologie-environnement

-

Gouvernement du Canada. (2024, 4 mars). Brûlages dirigés. Parcs Canada. https://parcs.canada.ca/nature/science/conservation/feu-fire/dirige-prescribed